Email jep40@cam.ac.uk for 40% Book reduction & Teachers’ notes for Literature Cambridge online courses:

*Odysseus the Storyteller, Weds 6 – 7.30pm UK time 5th Oct.-Nov.2022 https://www.literaturecambridge.co.uk/book-classical/course-odysseus

*The Aeneid Weds 11 Jan.-8 Feb.2023 [How] does Virgil translate Homer’s heroes? https://www.literaturecambridge.co.uk/book-classical/virgil-course

BOOK The Iliad and the Odyssey: The Trojan War: Tragedy and Aftermath Review Journal of Classics Teaching bit.ly/3R0TdV9 ‘ideal companion to Homer and his heroes’ Professor Barry Strauss, Cornell

CONTENTS

Book Summaries, analysis, key word sections, ‘Layers’, ‘Others’ Stories, Women’s Stories’

‘Heroic Values, Heroic Values’, ‘Heroic Bonds: Hektor and aidōs, the Wrath of Achilles’

‘Waiting for Odysseus’, ‘From Calypso to Phaeacia’, ‘Odysseus’ Stories’, ‘Return to Ithaca’

Index A People of the Iliad and Odyssey; Index B Greek Key words; Index C Themes and Contents

Q FOR DISCUSSION

‘The World of the Hero’: good title for the A Level Homer and Virgil course book but my teaching notes are all about different worlds – Troy citadel, Greek camp, Calypso’s island, Ithaca, Carthage, the Underworld, site of Rome.

And such different heroes, heroes’ mentality, values!

All layered into dramatic narratives with shifting perspectives, where the battlefield is a place of glorious endeavour and bloody waste, where a Hektor and an Aeneas can fight for heroic status yet be trammelled and trapped; where the founding of Rome can both beckon but also cost, where the enthralling storyteller become a bloody revenger.

Iliad– some key words running through narrative, for discussion:

Troy as a testsite of aretē? What is aretē?!

A Day in the Life, an aristeia (time of being first, pre-eminent) of a typical hero – Diomedes’ comic and tragic encounters in Book 5

Is kleos aphthiton, undying fame, worth dying for?

What is the story of the ‘Wrath, mēnis, of Achilles’?

Paris v Hektor shamelessness v bounded by shame aidōs

Valuing (?) women – Chryseis, Briseis, Helen as geras (material correlate, prize)

Odyssey

Everyone knows Odysseus’ stories, but what about Odysseus as a storyteller? How does he answer the challenge to all xenoi, guests, once rested, that they explain who they are and how their experiences have brought them here – tis pothen (who are you and how did you get to be that?)

How does he measure up to the ‘gold standard’ that he applies to the Phaeacian Bard, that he shapes his material kata kosmon, according to the [beautiful] order of things, and kata moiran, according to the shape of things, destiny.

And what about those whose stories he enters – Nausicaa, Calypso, Circe?

When Odysseus is landed back on Ithaca, he tells the disguised Athena a long ‘Cretan Tale’. Athene is overjoyed at his tricksiness, his subtlety, his alikeness to her – his ‘flexible presentation’ (poikilomētis) or ‘conman’ skills – but wonders that he does not rush to the Hall to his wife and son.

Instead he initiates a series of tests, adopting the persona of the ‘absent judge’ of folk story, returning to test and judge those he left behind. Meanwhile Penelope sets up a series of challenges for the Suitors and the unknown Stranger: she is Odysseus’ like-minded ‘other half’: homosphrosunē.

Aeneid – Does Aeneas get lost in translation?

At the start of the Aeneid, Augustus’ circle would hear Aeneas entangled with one of the great figures of literature – Queen Dido: a sympathetic figure but one created out of Calypso and Cleopatra. Aeneas constantly loses himself in translation – whereas Calypso, although complaining to Hermes about male gods’ anti feminism, works with Odysseus to send him on his way, Aeneas when alerted by Mercury to his forgotten mission, sneaks away without facing Dido.

And whereas Hephaistos crafts armour for Achilles, now, to die in, with all the beauty, joy and variety of the social and agricultural year, Aeneas will have to go into battle with Augustus literally on his shoulder.

Whereas Odysseus ends reunited with his life partner, Aeneas starts with losing his wife and city, is forced to leave his new found partner and kingdom and ends with the young fiancée of his enemy.

Most of all, his – and Augustus’ – preeminent quality, that of pietas, claimed and restated by Aeneas time and time again, even when replaying Achilles’ killing of priests and suppliants, chimes with and brings a dark resonance not with mēnis/furor-ridden Achilles but with the always [over] observant, aidōs-bound Hektor.

The Aeneid ends with a big question: will it end on an act of charis, graceful reciprocity, respecting the suppliant (Priam/Turnus) as the Iliad, or will Aeneas, seemingly for the first time, replay nothing but act agentively, in his own right?

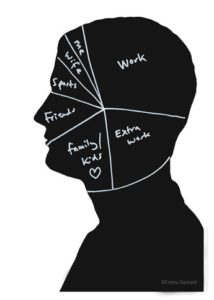

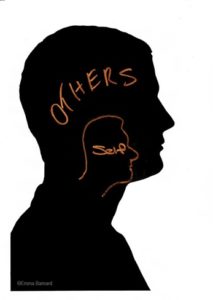

As an artist working collaboratively with doctors I feel privileged to have been given a fascinating insight into the field of medicine and I have a huge amount of respect for them, the work that they do and the immense pressure that they are under. In

As an artist working collaboratively with doctors I feel privileged to have been given a fascinating insight into the field of medicine and I have a huge amount of respect for them, the work that they do and the immense pressure that they are under. In