Difficult and Sensitive Discussions

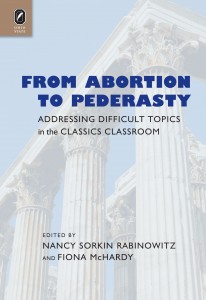

From the Introduction to From Abortion to Pederasty: Addressing Difficult Topics in the Classics Classroom by Nancy Sorkin Rabinowitz and Fiona McHardy (Editors) Ohio State University Press (2014)

Discussions of pedagogy on U.S. college campuses have emerged most often from the pressure to change the curriculum following Black power and women’s liberation movements, as well as more recently disability activism and gay and lesbian. While not all faculty members agreed that anything needed to change, in Women’s Studies the curriculum itself generated heightened awareness of the importance not only of the material covered but also of the methods of teaching. Feminist theory and critical pedagogy assume that knowledge(s) are situated and grounded in experience; feminism in particular pays special attention to the personal, noting the inadequacy of attending only to the public domain; finally, it is politically committed, viewing teaching as a means of making change and producing an alternate reality to the hegemonic vision.

Attending only to gender as a factor of analysis was itself critiqued early in the 80s by women of color; since that time, feminism has sought to put forth a complex analysis that takes into account race and class as they intersect with gender. Amie Macdonald and Susan Sanchez-Casal argue for a realist view of identity and an anti-racist pedagogy that takes into account “the complex networks of privilege and oppression that structure all of our identities” (Macdonald and Sanchez-Casal 2002, 5). They further argue that the emphasis on difference does not mean that there can be no objective knowledge: “it is only from within the examination of difference that we can reach for theory-mediated objectivity” (Macdonald and Sanchez-Casal 2002, 7). But if students simply take one course to fill a requirement—either a special diversity course, or a course in Women’s Studies, Latino Studies, or Africana Studies—it will not have a truly liberatory effect. Furthermore, the requirement carries its own risks, for instance, of ghettoization, with issues of diversity and minority politics confined to programs that are taken by self-selecting groups of students. Change comes slowly over time if at all and requires multiple approaches. Therefore, it is very important that students across the curriculum have the opportunity to learn how to engage with the differences that may be present in a text and in the classroom.[i]

For quite some time feminists within the academy have been trying to educate colleagues about the fact the traditional curriculum was, to put it bluntly, sexist; even introductory Latin and Greek text books can be exclusionary. In those new fields, particular attention was drawn to the examples given in text books. Hoover, for instance, comments about Latin textbooks that there is “an assumed audience for textbooks that excludes ethnic, racial, and gender diversity. But the representation of women is disturbing” (Hoover 2000, 58).

How do we change our teaching to take account of the different students in our classrooms? As Too, one of the editors of Pedagogy and Power, puts it, pedagogy was formerly “a dirty little secret, the fearsome and demeaned professional impropriety” but it has acquired more importance in the wake of these challenges to the demographics and the curriculum, in classics as well as in other disciplines. There is a realization that we must address what happens when we change the object studied and the subjects who are studying. Henry Giroux, a philosopher of education, argues that “What is at stake here is not simply the issue of bad teaching but the broader refusal to take seriously the categories of meaning, experience, and voice that students use to make sense of themselves and the world around them” (Giroux 1992: 125). In fact there is a question about how much we can allow our students to speak in “their own voice” in class (Kahn 2005: 1-7, esp.), given the requirements of the disciplines that we have been trained in.

As we think about pedagogy, we may, we must, recognize other ways to liberate the Classics from the past.